A last there is a modern book on the English Neo-Romantic artist Alan Sorrell. It was published to coincide with the exhibition of Sorrell's work at the Soane Museum. Another book Alan Sorrell: Early Wales Re-created,which I have discussed elsewhere was an excellent production and that is where I discuss his archaeological work.This one is in a larger format with several contributors from various disciplines.There is a useful chronology. So when I refer to "the writer" I am speaking about the author of a particular section of the work.

They don't make artists like this any more. If you wanted to find someone to do similar tasks in archaeological reconstruction nowadays you might be looking at an animation studio. Perspectives and fly throughs in a trice! But Sorrell could do perspective and lettering, anything you wanted really. He is a designer/ illustrator most definitely.And a complete professional in his field.

His Rome scholarship did not really lead too far artistically but meeting archaeologists at the school certainly did. Some simplification of the figure-coming from an enthusiasm for Piero was long lasting. His early subject paintings do not merit much enthusiasm to my mind. But they are a young man's work. The monochrome illustration of the Annunciation looks heavy and despondent. There is no joy in it. The painting Summer Scene Triptych with it's disturbing reds and greens is rather repellent. But then recent English artists have struggled with colour and I find no evidence in this book of an admiration for French work.

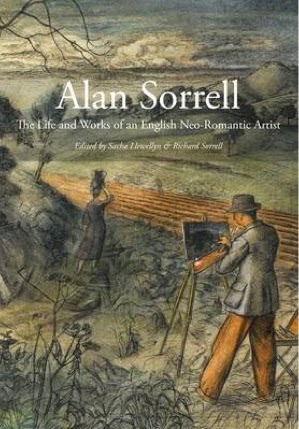

The book cover shows his watercolour The Artist in the Campagna. It is a curious item. It certainly doesn't resemble the work of those artists who a 100 years earlier flocked to portray the transcendental emptiness of this region strewn with ruins. My first thought was that the artist was portraying an English scene; not Italy.The Appian Way of 1932 is more striking and here we have Italy through a full blown, slightly incoherent, theatrical and very English Neo-Romanticism. Ruins and statues abound, a courting couple strolls into the painting.

I do think that Sorrell will be remembered most for his archaeological reconstruction work and for his book and guide book illustrations.As an archaeological illustrator his work is bold,dramatic, rich and generous. The writer does not state this and I think she should have done so.The aerial views which are such a consistent feature of his archaeological reconstructions seem to have developed from his war work with the RAF. The section on his war service has has some excellent work-again very dark-of camp life, parades etc.

His "sombre colour" was evident early on and noted by the Director of the British School.

Nevertheless his project Working Boats from Around the British Coast for the Festival of Britain certainly succeeds in a slightly jaunty and elaborate manner.It was the background to the bar on the ship which brought the Festival to ports in the UK.

Take for example The Seasons a school mural for Warwick. No one could do anything of such competence nowadays but the colour is very low key. The writer is surely correct in seeing some inspiration from Brueghel here but everything is really rather grey. This gives coherence, unity, and a kind of impact. But to eschew the riotous colours of an English Spring, the richness of Autumn and so on...... Well, unity and impact were obviously important.

Sorrell made a visit to Iceland in the thirties. The chronology in the book says it was in 1934, with his exhibition of resulting work occurring in 1935. The text says that the visit was in 1935 but an apparently signed drawing, illustration 118 is said to bear the date 1934. (He also met the writer Haldor Laxness). The works were on show in October of 1935* and so just might have influenced the Auden/Isherwood visit of 1936-though Sorrell was not the only artist showing Icelandic subjects in London at this time. Was there some interest in the Sagas on Sorrell's part? William Morris had also visited and Auden and perhaps Sorrell would have known about that trip. Or was it something specific to the Thirties? The products of this trip were-strong and bold designs with something of the clarity and hardness of contemporary wood engravings .

Sorrell's own autobiographical writings sound interesting.They are apparently pseudonomous. To me this suggests reticence rather than vanity. In this present book we don't get much sense of his personal character. That he was extremely hardworking and professional comes across clearly.His refusal to work on projects which might lead to the bombing of artistic centres is highly commendable.

But he had written of one of his early works ,"I always find it necessary to have information about every detail and incident in a work, and it is not by any means a source of pride but often of keen regret that I cannot improvise. Thus every individual leaf and all the curious bends of the tree trunks required as much study as the figures themselves." In his archaeological work this was something of an advantage and curiously enough he could let himself go once the structure was established and produce reconstruction work which has not been equalled.

*Oct 1935 per Times Digital Archive.

Alan Sorrell:The Life and Works of an English Neo-Romantic Artist, Edited by Sacha Llewellyn and Richard Sorell, Sansom & Co,2013

They don't make artists like this any more. If you wanted to find someone to do similar tasks in archaeological reconstruction nowadays you might be looking at an animation studio. Perspectives and fly throughs in a trice! But Sorrell could do perspective and lettering, anything you wanted really. He is a designer/ illustrator most definitely.And a complete professional in his field.

The book cover shows his watercolour The Artist in the Campagna. It is a curious item. It certainly doesn't resemble the work of those artists who a 100 years earlier flocked to portray the transcendental emptiness of this region strewn with ruins. My first thought was that the artist was portraying an English scene; not Italy.The Appian Way of 1932 is more striking and here we have Italy through a full blown, slightly incoherent, theatrical and very English Neo-Romanticism. Ruins and statues abound, a courting couple strolls into the painting.

I do think that Sorrell will be remembered most for his archaeological reconstruction work and for his book and guide book illustrations.As an archaeological illustrator his work is bold,dramatic, rich and generous. The writer does not state this and I think she should have done so.The aerial views which are such a consistent feature of his archaeological reconstructions seem to have developed from his war work with the RAF. The section on his war service has has some excellent work-again very dark-of camp life, parades etc.

|

| Harrow's Scar Milecastle:Hadrian's Wall |

Nevertheless his project Working Boats from Around the British Coast for the Festival of Britain certainly succeeds in a slightly jaunty and elaborate manner.It was the background to the bar on the ship which brought the Festival to ports in the UK.

Take for example The Seasons a school mural for Warwick. No one could do anything of such competence nowadays but the colour is very low key. The writer is surely correct in seeing some inspiration from Brueghel here but everything is really rather grey. This gives coherence, unity, and a kind of impact. But to eschew the riotous colours of an English Spring, the richness of Autumn and so on...... Well, unity and impact were obviously important.

Sorrell made a visit to Iceland in the thirties. The chronology in the book says it was in 1934, with his exhibition of resulting work occurring in 1935. The text says that the visit was in 1935 but an apparently signed drawing, illustration 118 is said to bear the date 1934. (He also met the writer Haldor Laxness). The works were on show in October of 1935* and so just might have influenced the Auden/Isherwood visit of 1936-though Sorrell was not the only artist showing Icelandic subjects in London at this time. Was there some interest in the Sagas on Sorrell's part? William Morris had also visited and Auden and perhaps Sorrell would have known about that trip. Or was it something specific to the Thirties? The products of this trip were-strong and bold designs with something of the clarity and hardness of contemporary wood engravings .

Sorrell's own autobiographical writings sound interesting.They are apparently pseudonomous. To me this suggests reticence rather than vanity. In this present book we don't get much sense of his personal character. That he was extremely hardworking and professional comes across clearly.His refusal to work on projects which might lead to the bombing of artistic centres is highly commendable.

But he had written of one of his early works ,"I always find it necessary to have information about every detail and incident in a work, and it is not by any means a source of pride but often of keen regret that I cannot improvise. Thus every individual leaf and all the curious bends of the tree trunks required as much study as the figures themselves." In his archaeological work this was something of an advantage and curiously enough he could let himself go once the structure was established and produce reconstruction work which has not been equalled.

*Oct 1935 per Times Digital Archive.

Alan Sorrell:The Life and Works of an English Neo-Romantic Artist, Edited by Sacha Llewellyn and Richard Sorell, Sansom & Co,2013